Patsy Shmatsy

Rethinking the most misunderstood phrase in modern history

I’ve just been reading Stephen King’s 11/22/63, which is the best popular novel ever written about the Kennedy assassination. (The best serious novel about the case is Don DeLillo’s superb Libra.) In King’s book, a guy living in the year 2011 finds a time portal that takes him back to the year 1958. This gives him a chance to alter the course of history — to prevent Kennedy’s murder, and thereby to avert (at least in theory) all the various historical catastrophes that happened as a consequence of it.

As the title of King’s novel reminds us, the Kennedy assassination didn’t take place until November 1963. So why does the book’s hero need to travel all the way back to 1958? As long as King was inventing a time portal that let his hero go back and save Kennedy, why not make the portal come out just a day or two before the assassination, instead of five years before it?

Well, one reason is that King wanted to write a novel, not a short story. He wanted to play around with all the possibilities of the time-travel device; he wanted to write a long narrative set in the late 50s and early 60s, steeped in the day-to-day phenomena of the Kennedy era.

There’s also the matter of narrative suspense. King’s hero, whose name is Jake Epping, doesn’t especially like the fact that he’s been given the chance to change history. Before he intervenes in it, he wants to make sure that his intervention will change things for the better. On the face of it, the simplest way for Epping to stop Kennedy’s murder would be to kill Lee Harvey Oswald — the man that history says pulled the trigger on November 22nd. If history is right about that, Epping’s task is straightforward. Kill Oswald at any point before 12:30 p.m. on the afternoon of the 22nd, and Kennedy will live. Job done.

But Epping is a morally serious person. He doesn’t take the idea of murdering Oswald lightly; he’s willing to do it only if it’s sure to save Kennedy. And like everyone else living in the year 2011, Epping has heard it said, ad nauseam, that there was a conspiracy behind the assassination. If there was a conspiracy, then killing Oswald won’t necessarily save the President. Maybe the other conspirators will go ahead and kill him anyway.

So before Epping takes the radical step of murdering Oswald, he needs time to reassure himself that Oswald, and Oswald alone, killed Kennedy. He needs to spend months tracking Oswald’s movements, making sure he doesn’t interact with anyone who looks like a possible confederate.

Epping also needs to eliminate a more haunting possibility: the possibility that Oswald was completely innocent, and had no hand in Kennedy’s murder at all. Epping has done his research. He’s read all the assassination literature, including conspiratorial books “stating with utter certainty that [Oswald] hadn’t pulled the trigger at all and was exactly what he called himself after his arrest, a patsy.” If Epping kills a man who was nothing more than a patsy, the results will be doubly calamitous. He will have murdered an innocent man; and the assassination of Kennedy will still go ahead and happen.

I won’t spoil King’s novel by saying any more about it. I recommend it, both as an excellent piece of speculative fiction, and as a fun primer on the true history of the Kennedy case. King knows his assassination lore; he weaves a lot of carefully researched facts into his fiction. Moreover, his head is screwed on right. He knows that in real life, the evidence of Oswald’s guilt is overwhelming. He knows that if Jake Epping is to find proof of some conspiracy, it will have to be fictional proof — proof that’s real enough in the speculative world of the book, but has no existence in the world beyond it.

Despite all of his careful research, King does get one thing wrong. And I don’t blame him for getting this thing wrong, because everybody gets it wrong. King misunderstands Oswald’s use of the word patsy. He thinks — as everybody thinks — that when Oswald called himself a patsy, he was claiming to be a wholly innocent fall guy. If there’s one thing that everybody “knows” about the Kennedy assassination, this is it. Lee Harvey Oswald claimed to be a patsy — as in, the victim of an immense frame-up.

But what if I were to tell you that Oswald never made this claim? It’s true enough that he did once — and once only — utter the phrase “I’m just a patsy.” But if you stick around for the remainder of this essay, I’m going to prove the following three things to you about Oswald’s patsy claim:

When Oswald made the claim, he meant something completely different from what we all think he meant.

Once you understand what Oswald really meant, it becomes plain that he was lying. I don’t mean that the patsy remark proved to be a lie later on; I don’t mean that the evidence subsequently showed that Oswald wasn’t a patsy (although it did). What I mean is that the patsy remark was an instant lie. It was a lie at birth. It was already manifestly untrue at the moment it came out of Oswald’s mouth.

Far from supporting the notion that Oswald was innocent, the patsy remark proves, all by itself, that he murdered Kennedy. Not that we need any further proof of this, mind you. Oswald’s guilt is one of the most lavishly proven facts in human history. But if we had no other evidence in the case at all — if we had no ballistics or medical or circumstantial or eyewitness evidence — I believe we could deduce Oswald’s guilt from the patsy remark alone, using pure logic. I think Oswald made a huge tactical and linguistic blunder when he uttered his patsy line. I think it amounted to an accidental confession that he killed Kennedy. And I think it gives us an important clue about why he did it.

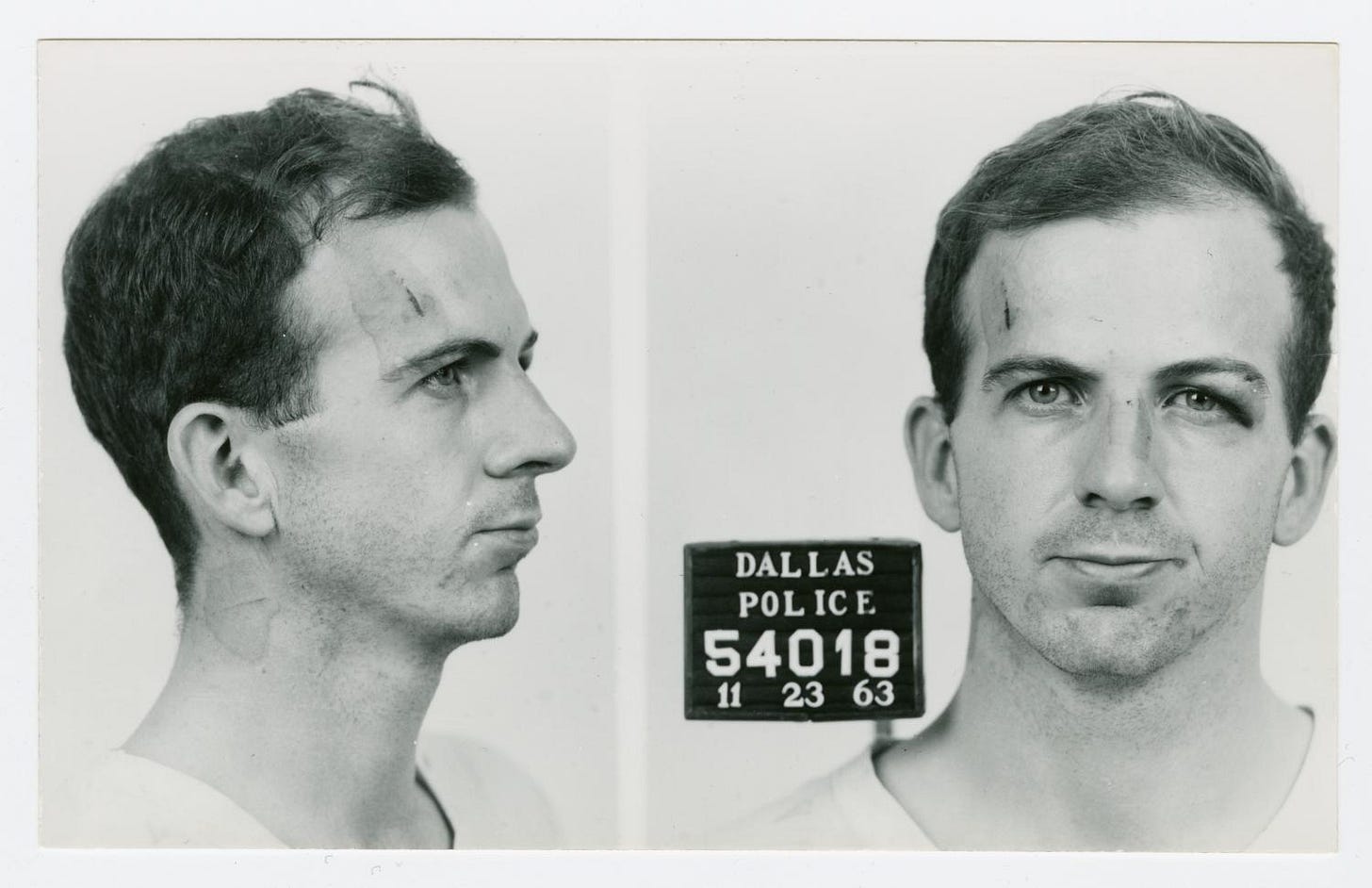

To start taking Oswald’s patsy remark apart, we need to understand the context he uttered it in. He delivered the famous line at 7:55 on the night of the assassination. He was in police custody at Dallas City Hall at the time, and was being led in handcuffs through a corridor packed with reporters. At this point in the evening, Oswald still hadn’t been formally charged with murdering the President. But he had been charged with another murder — that of a Dallas policeman named J. D. Tippit, who had been gunned down on a quiet street in the suburb of Oak Cliff at 1:15 that afternoon, 45 minutes after the shooting of Kennedy.

As the cops hustled Oswald through the crowded corridor, reporters peppered him with questions. Mainly they peppered him with one question. “Did you kill the president?” Footage of the moment can be watched here. When one reporter yelled the money question again — “Did you shoot the President?” — this was Oswald’s reply:

No, they’ve taken me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union. I’m just a patsy.

Before I go on, I need to stress that Oswald never referred to himself as a “patsy” at any other moment than this. He didn’t repeat the claim at any other time, in any other context. These two sentences are it. They’re the whole basis of our belief that Oswald was a patsy, or at least claimed to be one.

Of the two sentences I’ve quoted, the first sentence — the one about Oswald’s having lived in the Soviet Union — is infinitely less well-known than the second one. Conspiracy theorists love quoting the second sentence but don’t much like quoting the first one; and it isn’t hard to see why. The first sentence drastically waters down the meaning and significance of Oswald’s patsy claim. Indeed, you begin to wonder if Oswald even knew what the word patsy meant, when you hear his remark in its original context.1 A patsy is someone who’s been framed, someone who’s been elaborately set up to take the fall for something he didn’t do. That’s the usual meaning of the word; and it’s certainly what everyone thinks the word means in Oswald’s case. And not just in Oswald’s case. From the murder of RFK to the attacks of 9/11 to the massacre at Sandy Hook, the idea or myth of the wholly innocent fall guy is central to all of modern conspiracy theory. You could say that conspiracy theory doesn’t really work without the concept of the patsy. And Oswald has always been the poster boy for the concept. He’s the original patsy — the O.P.

But when you restore Oswald’s patsy claim to its true context, it becomes clear that he wasn’t using the word in anything like that sense. He wasn’t claiming that some sinister group or agency had framed him because he’d once lived in the Soviet Union. He was claiming that the Dallas cops had “taken him in” for that reason. He was using the word “patsy” in a very mild and limited sense — as if it meant “a convenient man to arrest”, rather than “a convenient man to set up in advance as the fall guy for an incredibly elaborate assassination plot”.2

Why do we persist in believing that Oswald meant the second thing rather than the first? Mainly we believe it because conspiracy theorists have worked very hard to make us believe it. They have torn Oswald’s claim out of its original context and rinsed the dirt off its roots. They have tidied his words up in post-production. They have made Oswald seem to say what they wish he’d said, instead of what he really did say.

And they have a good tactical reason for doing this. The smarter Kennedy conspiracists have always understood that the evidence of Oswald’s guilt is overwhelming. They know that there’s only one conceivable way he could have been innocent, despite the mountainous evidence of his guilt — and that’s if the real assassins carefully fabricated this mountain of evidence specifically in order to set Oswald up. “Just maybe, Oswald’s exactly what he said he was, a patsy,” says Kevin Costner in Oliver Stone’s fatuous movie JFK. Later on in the film, Costner elaborates on this idea. “Lee Oswald must’ve felt like Joseph K. in Kafka’s The Trial,” he says. “He’s never told the reasons for his arrest. He doesn’t know the unseen forces ranging against him.”

When you compare Oliver Stone’s fever-dreams about the nature and extent of Oswald’s patsydom with what Oswald himself said on the matter, you notice something interesting. Stone was making far larger claims on Oswald’s behalf than Oswald ever bothered to make himself. When Oswald declared himself to be “just a patsy”, he wasn’t claiming that unseen forces had sinisterly arranged the evidence so that every last scrap of it pointed to him. On the contrary. He was talking as if the evidence didn’t point to him. He was saying the police had “taken him in” for no better reason than that he’d once lived in the Soviet Union. He was refusing to admit that the evidence even looked bad for him. He was making it sound as if this was all just a routine misunderstanding that would soon be cleared up.

In other words, Oswald was lying. He was childishly denying the realities of the case against him; and he was brazenly forgetting to mention the laundry-list of fantastically incriminating things he’d done in the hour after Kennedy’s shooting. And if Oswald could only protest his innocence by telling laughably obvious lies, that seems a fair sign that he wasn’t innocent. By any sane measure, the Dallas police had had excellent objective reasons for arresting him that afternoon. Straight after Kennedy was shot, Oswald had done the following things. He had fled the Texas School Book Depository; he had traveled by bus and then taxi to his small rooming house in the suburb of Oak Cliff; and he had hurried inside to change his clothes, grab his loaded .38 revolver, and cram a handful of spare rounds into his pocket.

And that was by no means all he did. After leaving the rooming house he cranked his suspicious behavior into overdrive, in ways that we’ll get to in a moment. But already it should be clear that Oswald, in the immediate wake of Kennedy’s shooting, did stuff that would have piqued the interest of even the dullest police force. Only two basic explanations for his behavior spring to mind. One is that he was as guilty as sin. The other is that he was innocent — but somehow sensed, from the moment Kennedy was shot, that he had been set up to take the fall.

This is the only innocence scenario that even remotely makes sense, given the immense weight of the evidence against Oswald, and given the way he instantly scarpered from the scene of the crime. To believe Oswald was innocent, you have no choice but to believe that he was a patsy in the full Oliver Stone sense of the concept. And you have to believe that Oswald himself was aware of this straight away, from the moment Kennedy was shot.

And yet Oswald himself never claimed to be that kind of patsy. He was given multiple chances to make this claim, if it was true. The Dallas police repeatedly paraded him in front of the press, very generously affording him the opportunity to tell the world his story, if he had one. But on each of those occasions Oswald conspicuously failed to say that he had been stitched up, or framed, or set up to take the fall. And if Oswald himself didn’t claim to be a patsy of that kind, he wasn’t one. That’s really the end of the story, or at least it should have been. The conspiracists’ “patsy” idea was a washout from the start — it’s such a ridiculous pipe dream that even Oswald himself didn’t bother throwing it out there.

Why didn’t he? He said plenty of other ridiculous things while he was in custody. So why didn’t he say that? Why did he fail to offer up the only innocence narrative that would have made any sense? Why did he choose, instead, to make the demonstrably false claim that he’d been arrested because of his political past?

This is an interesting question, and I’ll come back to it. But for now, let’s stick with the text of Oswald’s patsy statement. Already we can see that it’s a kind of double embarrassment for the conspiracy theorists. For a start, it was an obvious lie, which childishly flew in the face of reality. Worse yet, even when he was freely just making shit up, Oswald still didn’t claim to be the right kind of patsy — the kind of patsy that the conspiracy theorists want and need him to have been.

And we haven’t even talked yet about the circumstances of Oswald’s arrest. When you consider how and where and why the man was apprehended, his patsy claim becomes truly hilarious. “They’ve taken me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union,” Oswald said. Taken me in? Oswald hadn’t been “taken in”, in the customary sense of that phrase. He hadn’t been peacefully tracked down at his home address, as part of a routine squeeze of local lefties. He had been violently apprehended in the Texas Theater, seven blocks away from the site of J. D. Tippit’s murder. The cops who’d arrested him there didn’t have the faintest idea of who Oswald was. They didn’t even know his name, much less that he’d once lived in the Soviet Union. They didn’t know where he lived now, let alone where he’d lived two years ago. They’d arrested him because he was a desperate-looking man who’d been seen breathlessly running into a theater after the shooting of a cop.

To put it another way, Oswald hadn’t been arrested because of who he was, but because of what he’d done. Straight after Tippit was shot, news of the incident went out over police radio, and the Oak Cliff area was inundated with cops. Squad cars sped up and down the town’s main street with their sirens blaring. While this commotion was happening, a local shoe store manager named Johnny Brewer noticed a man looking into the window of his store. The man was breathing heavily, as if he’d just been running. He looked scared. His hair was messed up. The tail of his brown shirt was hanging out, and a couple of its buttons were undone. Everybody else on the sidewalk was watching the passing police cars; but the guy in the brown shirt seemed to be deliberately keeping his back to them.

When the coast was clear, the guy in the brown shirt turned away from the window and moved quickly off down the sidewalk. Johnny Brewer stepped outside to watch where he went. Fifty yards down the street, the man turned and headed into the Texas Theater, slipping past the distracted box-office attendant. Brewer made his way down to the theater. While he guarded the exit, the box-office attendant called the cops. When they arrived, they entered the theater through the front and rear doors, turned the lights up, and got Brewer to point out the man he’d seen behaving oddly on the street. As the cops moved up the aisle toward him, the man stood up and said, “Well, it’s all over now.” He then punched the nearest cop in the face and drew a .38 revolver from his waistband. There was a scuffle. The suspect pulled the trigger of his gun, but a cop managed to stop the shot by jamming the flesh of his hand between the weapon’s cylinder and firing pin.

The man in the brown shirt was, of course, Oswald. And at this point, just for a laugh, we may wish to remind ourselves of Oliver Stone’s idiotic claim that Oswald was “never told the reason for his arrest.” Perhaps the arresting officers thought he could work that bit out for himself. More to the point, they still didn’t know that Oswald was Oswald. All they knew was that he was some random prick in a brown shirt who a) had been seen behaving suspiciously on the street in the wake of a policeman’s murder; and b) had sucker-punched and attempted to blow away a second cop in the course of being arrested. After being cuffed, Oswald was frog-marched out to a waiting car. In the car, on the way to City Hall, a detective asked him what his name was. He refused to answer. The detective pulled a wallet from Oswald’s pocket and found two ID cards in it. One said his name was A. J. Hidell. The other said his name was Lee Harvey Oswald. Only when he was down at police headquarters did Oswald finally cough up his real name.

All this makes a mockery of Oswald’s claim that “they’ve taken me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union.” And remember, this assertion was the logical premise of his patsy claim. They’ve arrested me only because I once lived in the Soviet Union. Ergo, I’m just a patsy, in the sense of being a convenient suspect to take in. But in truth, Oswald plainly hadn’t been taken in because he’d lived in the Soviet Union. Ergo, using Oswald’s own logic, he wasn’t really a patsy, in any sense of the word at all.

Behind closed doors, during his interrogations at City Hall, Oswald didn’t bother pretending that the cops had brought him in because he’d lived in the Soviet Union. He knew this claim was untrue; and he knew the cops knew it too. The patsy line was strictly for the cameras. It was just an ad hoc lie that Oswald probably forgot thirty seconds after saying it. If he did remember saying it, he had to know the claim would crumble to bits as soon as the facts about his arrest became generally known. He couldn’t have imagined, in his wildest dreams, that he would soon acquire an army of fans who would devote their whole lives to denying and avoiding the staggeringly obvious fact of his guilt. Oswald may have been nuts; but he wasn’t nuts enough to foresee that.

So the patsy remark was a lie, and a pretty pathetic one at that. But it wasn’t just a lie. It was a very weird lie. It was a lie that made no sense, given the hectic and sordid circumstances of Oswald’s arrest in the Texas Theater. One thing we know for sure about the Kennedy case — one thing that not even the conspiracy theorists can deny — is that Oswald was present at his own arrest. And yet the details of his arrest seemed to have quite eerily slipped his mind, when he claimed to have been “taken … in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union.” That’s the kind of arrest that a police force might plausibly make when seeking the killer of a president. But it’s hardly the kind of arrest they’re going to make when hot on the trail of a common criminal who’s just shot a cop. Oswald was talking as if the murder of J. D. Tippit had never happened — which was strange, considering that Tippit’s murder was, as of 7:55 p.m., the only crime Oswald had so far been charged with. He wouldn’t be charged with the President’s murder until almost midnight. Oswald was talking as if things were the other way around, as if the only murder he’d been charged with was Kennedy’s — as if he’d been arrested not because of his desperate and rat-like behavior in Oak Cliff, but because he was Lee Harvey Oswald, international left-wing man of mystery.

What was going on in Oswald’s head when he uttered this strange non sequitur — this curiously incongruous lie? We can only speculate. But I think we’re entitled to, and even obliged to. The dissonance between Oswald’s words and reality is so jarring that we have to resolve it somehow; we have to understand what made him say something so downright weird.

Here’s how I explain what Oswald said. His words made no sense in the world he uttered them into — a world in which he’d been arrested on suspicion of shooting a cop. But they would have made sense if the afternoon had panned out in a neater way — if it had featured the murder of Kennedy only, with no messy additional murders afterward. In the real world, things hadn’t happened like that. But it seems fair to conjecture that they had happened that way in the world of Oswald’s imagination, as he fantasized about his crime in advance. In Oswald’s ideal version of the afternoon, the Tippit complication wouldn’t have figured. Had the day gone according to plan, Oswald would have shot Kennedy, and Kennedy only. In that Tippitless alternative world, the patsy line — “they’ve taken me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union” — would have made logical sense. It still wouldn’t have been true. But at least it would have made sense. It’s the kind of line a man would plan on delivering, if he imagined that killing the President, and being arrested and tried for that offense, would make him an international left-wing hero or cause célèbre — like Alger Hiss, or the Rosenbergs, or Sacco and Vanzetti.

The mysteries of the patsy remark are resolved once you’ve grasped that it was a line prepared before the event. And if the line was concocted in advance, it delivered accidental proof, from Oswald’s own lips, that a) he murdered Kennedy; b) Kennedy’s murder was a pre-meditated political act; and c) the crime was motivated by Oswald’s dream of becoming an international revolutionary hero — the same dream that had once prompted him to move to the Soviet Union. Again, it’s not as if we need further proof of any of these things. We’ve already got proof of them up the yinyang. But I do find it quite funny that the patsy remark, which has been so strenuously quoted and fetishized over the years by people who think Oswald was innocent, actually turns out, on examination, to offer neat proof, from the lips of no less an authority than Oswald himself, that he was as guilty as hell.

To back up my reading of the patsy remark, I want to quote something Norman Mailer wrote, in his brilliantly insightful Oswald’s Tale. Mailer believed, as I do, that Oswald had a kind of ideal version of Kennedy’s assassination in his head, which fell to pieces as a result of his unforeseen encounter with J. D. Tippit. In Mailer’s view, Oswald dreamed of standing trial after the assassination, and delivering grand political speeches from the dock — just as his hero Fidel Castro had done in 1953, when being tried for treason in Cuba. Mailer writes:

The first element in the loss of an heroic trial became the four shots he fired into Tippit. There can be no doubt that he panicked. As soon as he killed Tippit, the mighty architecture of his ideology, hundreds of levels high and built with no more than the game cards of his political imagination, came tumbling down. He knew Americans well enough to recognize that some might listen to his ideas if he killed a President, but nearly all would be repelled by any gunman who would mow down a cop, a family man — that act was small enough to void interest in every large idea he wished to introduce. By killing Tippit he had wrecked his grand plan to be one of the oracles of history.

Earlier on, I raised the question of why Oswald never claimed to be a patsy in the “right” sense. As long as he was making shit up, why didn’t he go the whole hog, and claim that some sinister person or agency had gone to elaborate lengths to frame him? In light of all the available evidence, this was the only innocence narrative that was ever going to fly. So why didn’t Oswald himself run it up the flagpole?

One possibility is that he just wasn’t thinking straight. Maybe Mailer is wrong, and Oswald had no coherent plan beyond the shooting of Kennedy. Maybe he was the dog that caught the car. Once he’d caught it, maybe everything after that was a blur.

Another possibility is that Oswald knew he would be wasting his breath. He of all people knew that there wasn’t a shred of reasonable doubt about his guilt. So why bother thinking too hard about cover stories? He could hardly have guessed that a cult of unreasonable doubt would soon attach itself to the case like a limpet, with disastrous consequences for America’s long-term mental health.

But if Norman Mailer was right about Oswald — and I think he was — another possibility arises. Maybe Oswald didn’t particularly want the world to think him innocent. Yes, he would play the childish game of denying his guilt to the police and the FBI. And it’s a supremely fair bet that he would have pled Not Guilty if he’d lived to be indicted — not because he was nuts enough to think he would be found Not Guilty, but because a trial would have prolonged his moment in the sun. Oswald was a man who’d been waiting, all his life, to assume what he considered to be his rightful place at the center of world affairs. Finally he was there. And after all, what was the point of single-handedly murdering the most powerful man in the world if the world didn’t believe he’d done it?3

Was Oswald aware of the word’s commonly accepted meaning? It’s impossible to know for sure, but I wouldn’t want to bet on it. Oswald was a poorly educated man; his friend George de Mohrenschildt once called him a “semi-educated hillbilly.” So it seems eminently possible that Oswald simply didn’t know what the word “patsy” meant. Maybe the whole mythology of Oswald’s patsydom has been built on a simple malapropism.

This part of my argument is not original, by the way. Other writers before me have insisted that the “Soviet Union” part of Oswald’s patsy remark matters, and undermines the commonly understood meaning of his claim. My own first encounter with this important point came when I read page 841 of Vincent Bugliosi’s endlessly useful book Reclaiming History.

I have told the complete story of the Kennedy assassination, and of all the myths and bad thinking it gave rise to, in my podcast Ghosts of Dallas, available wherever you get your podcasts.